Ending the “forever wars” – MIU’s Dr. Robert Schneider proposes “peace through health” paradigm shift

The “forever wars” need not go on forever. The path to peace lies in health. And the path to health runs through practical meditation techniques that not only foster individual health but create peace on a broad social scale, through the mechanism known as the Maharishi Effect.

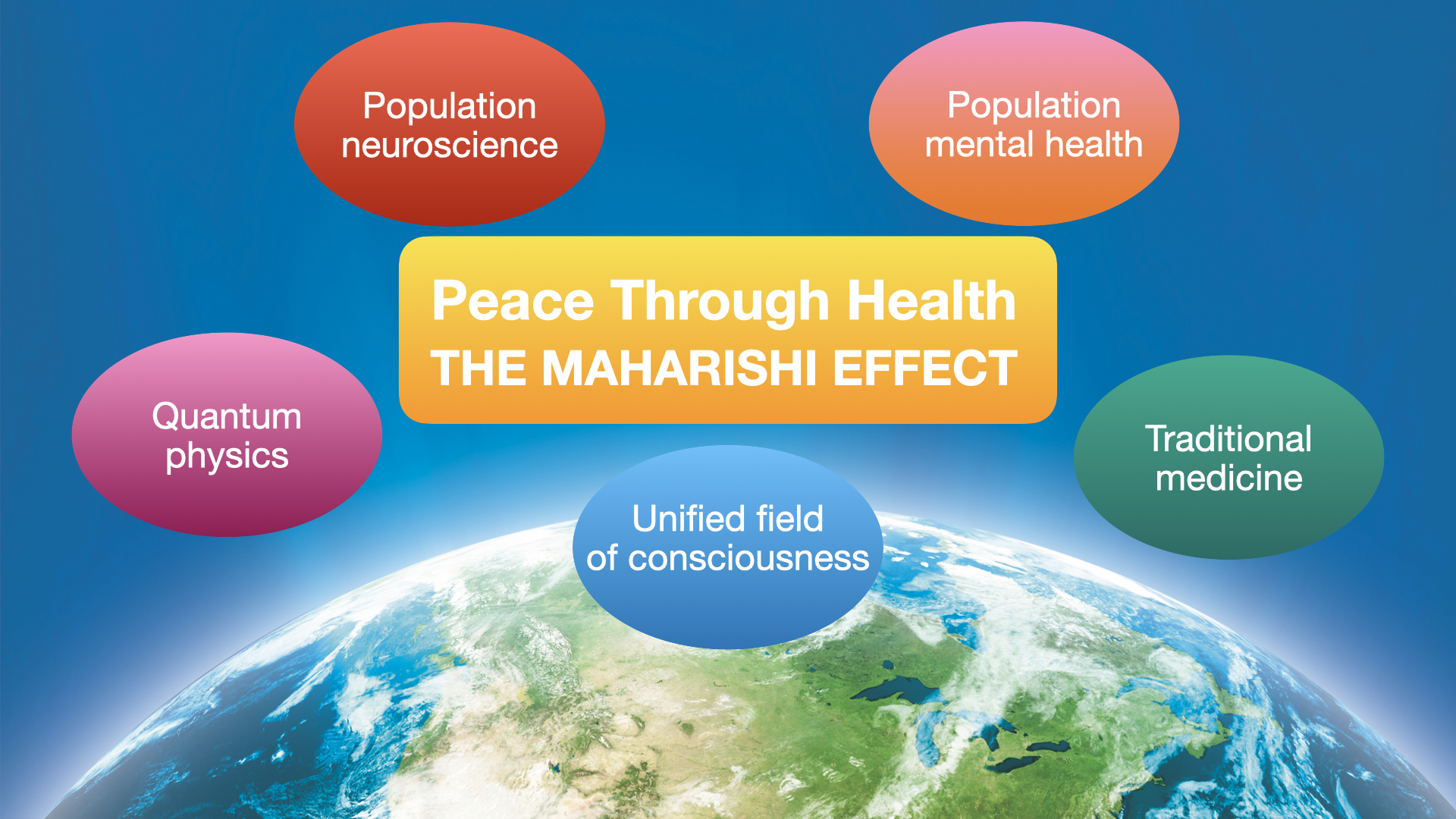

This is the thesis put forward by Dr. Robert Schneider and his coauthors in a perspective article about the Maharishi Effect entitled “Peace Through Health: Traditional Medicine Meditation in the Prevention of Collective Stress, Violence, and War,” recently published by Frontiers, the prominent research publisher and open science platform.

“This is the first time, to my knowledge, that a paper about the Maharishi Effect has been published in a fairly highly respected, mainstream public health and medicine venue,” Dr. Schneider says. Dr. Schneider, MD, FACCD, is Dean of the College of Integrative Medicine, Director of the Institute for Natural Medicine and Prevention, and Professor of Physiology and Health at MIU.

The paradigm barrier

The first study on the Maharishi Effect was conducted just over fifty years ago, showing reduced crime rate in four US cities where the percentage of the population practicing the Transcendental Meditation technique had reached the one percent threshold, which Maharishi Mahesh Yogi predicted would improve overall quality of life.

Since then studies on the Maharishi Effect have proliferated, expanding the scope of the original study to larger and larger populations, testing the effect in locations around the world, and identifying reductions in many other symptoms of social stress, including infectious diseases, accidents, and drug and alcohol and tobacco use. Perhaps most encouraging have been the studies showing reductions in international terrorism and warfare.

To date nearly sixty studies have been conducted, published in nearly thirty peer-reviewed scientific and scholarly journals.

“And yet, after fifty years and all this research, we still have not seen a large-scale implementation,” Dr. Schneider said. “We think this must be because it’s difficult for many people to understand how the Maharishi Effect works. How can people sitting with their eyes closed in a hotel in Jerusalem, for example, reduce the fighting in the Lebanon Civil War across the border to the north, as happened in that dramatic experiment in 1983? To many people this just doesn’t seem plausible.”

This is because the Maharishi Effect inhabits an entirely different paradigm, a different way of understanding how the world works, Schneider says. “Your paradigm or worldview shapes what you believe is possible and not possible, and in the prevailing materialist or physicalist worldview, this phenomenon is impossible.”

Enter doctors and health professionals — Peace Through Health

Dr. Schneider and company resolved to find a way to penetrate the paradigm barrier, to explain the Maharishi Effect in a way that professionals and policy makers could understand.

Fortunately, new developments in medicine and science have made that task easier. “Science is catching up to the Maharishi Effect,” Dr. Schneider says.

Schneider and his coauthors — Dr. Michael Dillbeck, Dr. Gunvant Yeola, and Dr. Tony Nader — began by framing the Maharishi Effect as part of the “peace through health” movement.

“This movement is gathering strength and attention,” Dr. Schneider says. “Since no one else has solved the war problem, including the prospect of nuclear war, doctors and health professionals have stepped into the game, saying we should do it. Just this past year top medical journals have been advocating for this approach — the New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of the American Medical Association, the Lancet, and the British Medical Journal.”

It’s well known that wars are catastrophic for health. As Dr. Schneider and company observe in the article:

“War and armed conflicts cause severe damage to public health through widespread injuries, diseases, disabilities, premature deaths, displaced populations, environmental contamination, and often violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. Moreover, it redirects crucial resources from health and social services to conflict-related activities, potentially perpetuating further violence.”

“But the converse is also true,” Dr. Schneider notes. “Poor health, particularly mental health, causes wars. That’s the message of the new medicine.”

Currently four major wars are underway, along with a long list of minor armed conflicts. Leading scientific minds consider these conflicts to be “intractable.” The current Israel-Palestinian hostilities, for example, are merely the latest installment in a 75-year conflict.

Looking to traditional medicine

The World Health Organization is also talking about peace through health — with a twist.

“The WHO is saying that not only is war bad for your health, but bad health creates conditions that give rise to war, and therefore the health professions should do something about it,” Dr. Schneider says. “And now they’re saying that since modern medicine hasn’t been successful in addressing this — or in addressing chronic, intractable individual health issues, for that matter — we should look to traditional medicine. Traditional medicine may hold secrets to modern maladies, they’re saying, and it’s cheap and used by billions of people already. So we should investigate it.”

That’s exactly what Dr. Schneider and his colleagues have done.

“We looked into the traditional medicine of India, Ayurveda, where there’s a long tradition of public health for prevention of epidemics and wars,” Schneider says. “Ayurveda describes how to reduce collective violence and prevent wars by managing the minds or consciousness of the people in the affected society. This challenge — known today as public or population mental health — is the theme of the Frontiers issue featuring our paper.”

Population mental health

We traditionally think of mental health as an individual malady. But some physicians have expanded this thinking to include whole societies — an example of how modern medicine is catching up to the theory behind the Maharishi Effect, making it easier to understand.

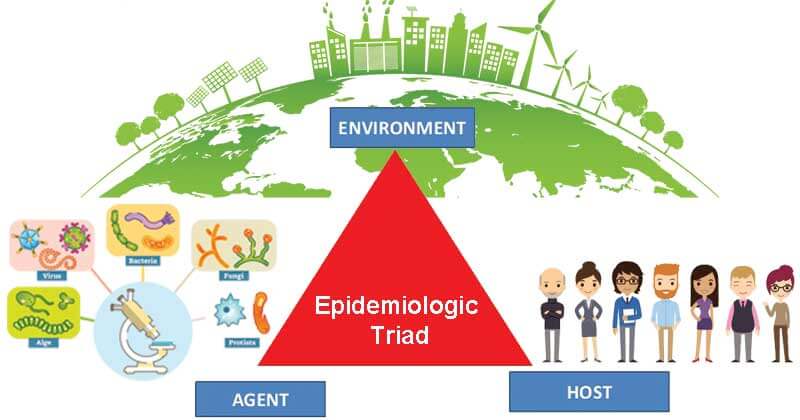

For example, scientists have developed a classic model called the Epidemiologic Triangle for studying health problems. The model involves three elements: the agent (the microbe that causes the disease), the host (the organism harboring the disease), and the environment (the external factors that enable disease transmission).

Barry Levy, a physician, epidemiologist, and author at Tufts University, has adapted this model to help understand collective violence. In Levy’s model, the host is the people, the environment is the conditions in which people live, and the agent is the machinery of warfare — military, weapons, the military-industrial complex.

“Levy proposes that to prevent war, we need to change the people,” Dr. Schneider says. “This contrasts with conventional approaches — for example, changing the agent by making weapons more or less available or militaries larger or smaller, or changing the environment by providing aid, modifying laws, enhancing security, and so on. The idea of changing the people is a huge step of progress.”

Dr. Schneider and his colleagues take Levy’s proposal another step forward.

“We extend the idea of Peace Through Health by proposing to change people from deep within — to expand their consciousness, literally to change the way their brains function,” Dr. Schneider says. “More integrated and coherent brain functioning will lead to changes in the environment and then to changes in military action — the agent — effectively going around the triangle in the opposite direction.”

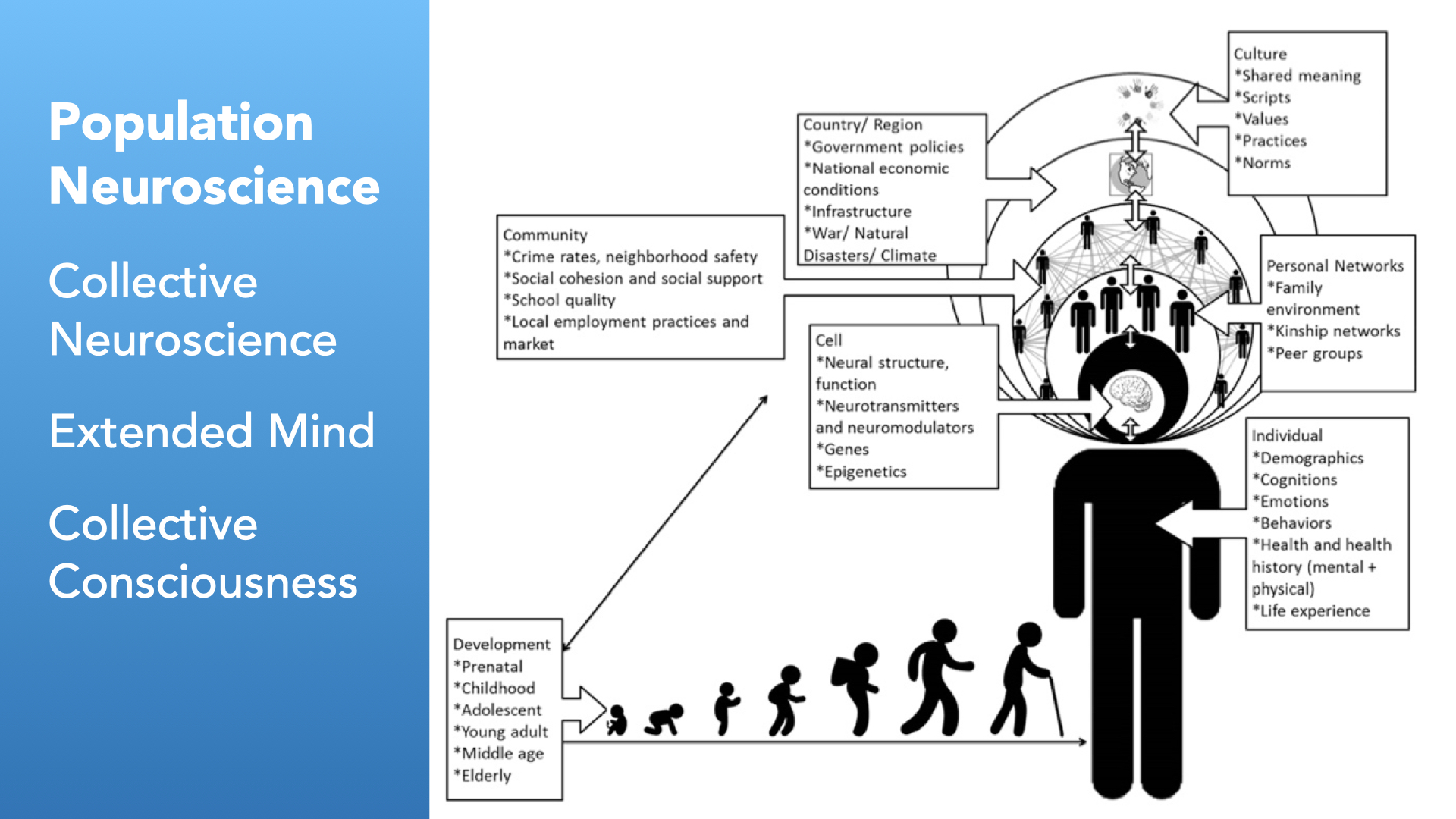

Population neuroscience — a breakthrough in public health

The new field of population neuroscience also makes the Maharishi Effect easier to grasp.

“Population neuroscience or collective neuroscience says that our cognitions — our thoughts and feelings — are connected, and we can measure that,” Dr. Schneider says. “In other words, there is such a thing as collective consciousness. We’ve been using this concept all along in describing the Maharishi Effect, but now there’s a growing empirical basis beyond the research on the Maharishi Effect itself.”

“Several Maharishi Effect studies show that group TM practice synchronizes brain activities across individuals,” Dr. Schneider says. “These findings help explain the increased social coherence and reduced stress-related behaviors we see in other Maharishi Effect studies — and they fit right into the new field of population neuroscience, shedding light on how collective meditation can neutralizes social stress, the basis of conflict and war.”

The perspectives of quantum physics and consciousness

The Frontiers paper also points to quantum physics — particularly the phenomena of interconnectedness and nonlocality — that can help explain the Maharishi Effect. “The Maharishi Effect shows that we humans are fundamentally connected at a deep level and that we can influence each other from thousands of miles away,” Dr. Schneider says. “While this idea may seem implausible in classical physics, interconnectedness and nonlocality define the quantum world.”

Finally, the authors describe the emerging understanding that consciousness is not limited to the brain but is an underlying, universal field that underlies the quantum dimension and connects everything and everyone. Dr. Nader’s new book, Consciousness Is All There Is: How Understanding and Experiencing Consciousness Will Transform Your Life, provides perhaps the most thorough and detailed explanation of this to date.

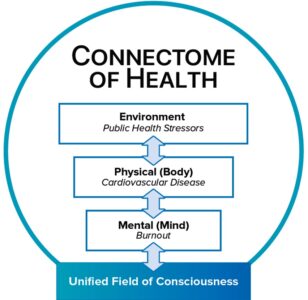

A new model of holistic health, a new paradigm for peace

“Having laid all this groundwork, then we put it all together in a new model of holistic health — the Connectome,” Dr. Schneider says. “Environment-body-mind-spirit/consciousness are all connected. This total health mental model has rarely been presented in our own science.”

In the prevailing paradigm of social science and conflict resolution, the remedies for war typically involve ceasefires, peace treaties, mutual consent, third-party mediation — external actions.

“The practice of group meditation for peace represents a paradigm shift from an external locus of change to an internal one, where cultivating inner peace within individuals can lead to positive outcomes on a societal scale.”

“The practice of group meditation for peace,” the Frontiers article says, “represents a paradigm shift from an external locus of change to an internal one, where cultivating inner peace within individuals can lead to positive outcomes on a societal scale.”

The paper has generated considerable media coverage, especially in India.

“With research on the Maharishi Effect continuing to be published, and with science and medicine gradually catching up to the Maharishi Effect by helping explain the findings, we’re not completely alone in the world anymore,” Dr. Schneider says.

Dr. Schneider and colleagues hope to call attention to the Maharishi Effect among a wider audience — in science, medicine, and public policy.

“If we can provide a comprehensive understanding of the Maharishi Effect, in terms that scientists can increasingly relate to, we can call for courage in overcoming cognitive bias, for making a paradigm shift, and for expanding public health policy to support this promising approach to peace. Maybe it’s time to end the wars.”

* * * * * * *

About the authors

- Robert Schneider, MD, FACC, is Dean of the College of Integrative Medicine, Director of the Institute for Natural Medicine and Prevention, and Professor of Physiology and Health at Maharishi International University.

- The late Michael Dillbeck had been a professor of psychology and member of the board of trustees at MIU.

- Gunvant Yeola is the principal at DY Patil College of Ayurveda and Research Center, Pune, Maharashtra, India.

- Tony Nader, MD, PhD, MARR, is the director of the Dr. Tony Nader Institute for Research on Consciousness and Its Applied Technologies at MIU, as well as the leader of the worldwide Transcendental Meditation organizations and author of the forthcoming book Consciousness Is All There Is.

Images

- Epidemiologic Triad, “Disease Control and Prevention,” Indiana Department of Correction.

- Population neuroscience, E.B. Falk et al, “What is a representative brain? Neuroscience meets population science,” PNAS, September 11, 2013.